Dr. Grace Gámez is a Program Coordinator at American Friends Service Committee – Arizona where she directs Reframing Justice, an advocacy platform for people impacted by the criminal legal system and mass criminalization. Dr. Gámez uses multimedia storytelling, theater, inside/outside coalition building, and community outreach to position directly impacted people to challenge the narrative around justice in Arizona. These efforts focus on shifting considerations from models rooted in punishment towards ones that embrace radical community-making and healing.

Dr. Gámez is a member of RTI International’s (RTI) APPR Advisory Board. This interview was conducted by RTI’s Racial and Community Justice Committee.

RTI: Please tell us about your community partners in Barrio Centro, Tucson, AZ.

Dr. Gámez: Barrio Centro is a neighborhood in Tucson, AZ, and largely consists of young, Latinx residents. The area is considered a food desert and is under-resourced and heavily policed. Flowers & Bullets is a local collective which has a Midtown Farm located in Barrio Centro that has become the hub of the neighborhood. This farm is important because, in addition to hosting community workshops on a range of subjects, including sustainability, it creates dignity, purpose, and a sense of belonging among the community members. Where dignity, purpose, and belonging are present, so is safety. Though not specifically conceptualized as an alternative safety project, the farm operates in practice as such and stands in sharp contrast to state-led “secure communities” projects.

RTI: We’re eager to hear more about your collaborative research with Flowers & Bullets.

Dr. Gámez: I collaborated with Flowers & Bullets to design a research project to assess what safety means to folx [1] from the community. We surveyed 171 community members on how they defined safety and what safety looked like to them. Our questions were made available in English and Spanish and responses were coded thematically. The data collection also included a photo elicitation[a] component (PEI) [2], which is a research method that provides an opportunity for collective theorization. [3] Members of the Flowers & Bullets collective were asked to submit photos of what safety looked like to them. This research was collaborative, and PEI offered an opportunity for members of the collective to highlight their unique analysis of safety and share what is meaningful in their lives.

RTI: How did this community define safety?

Dr. Gámez: The neighborhood defines safety as access to quality food, open spaces, healthcare, good schools, playgrounds, lights, sidewalks, etc. Safety was not defined by more law enforcement presence in their already highly policed neighborhood. Safety was also described as having access to spaces where people can gather for events like block parties, BBQs and potlucks. Everything that community members said creates a sense of shared safety is found in the work of Flowers & Bullets. Flowers & Bullets advocates for city investment, such as streetlamps and “pocket parks,” and they also host community events. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, each spring they would have a barbacoa (community BBQ/potluck). The neighborhood would come together at the farm, listen to music, play, and break bread together. For many, safety means the unhindered opportunity to build relationships with neighbors, because if you know your neighbors, you can talk to them about anything, including the needs of the neighborhood and community at large.

RTI: How did community members feel about being asked to participate in this study?

Dr. Gámez: I believe they appreciated being asked to participate and readily did so. I think it helped that I am from the community – I grew up in South Tucson. Also, people were excited to participate because Flowers & Bullets is a trusted face in the neighborhood and in the greater Tucson community. Oftentimes, our communities are not asked systems-level questions, and by using PEI I was able to evoke a different response than one might receive using traditional, close-ended survey questions. It was also important for me to acknowledge that for many, there is a shared feeling that we don’t have a justice system, but rather a punishment system. Many of us take for granted that this system works and is a fixed component of our society. But it doesn’t, and anything made can be unmade. Voicing that nuanced understanding, and being directly affected myself, I think adds to my credibility.

RTI: What preparations did you make to interview this community?

Dr. Gámez: For starters, I was intentional about the language I used in every step of the process. I’m always cautious about the words I use in any type of data collection or interaction with the community, careful not to trigger a systems-level response. For example, I may ask, “What does it mean to be in a healthy, thriving community?” versus a more negative framing of, “Do you consider your community healthy, safe or thriving?” I then dig deeper if need be to uncover additional information. Doing so led me to a better understanding of what safety means to this community. Additionally, I engaged the Flowers & Bullets collective early on and drew on their expertise when constructing the research, plus I sought their help to conduct some of the data collection for additional community buy-in.

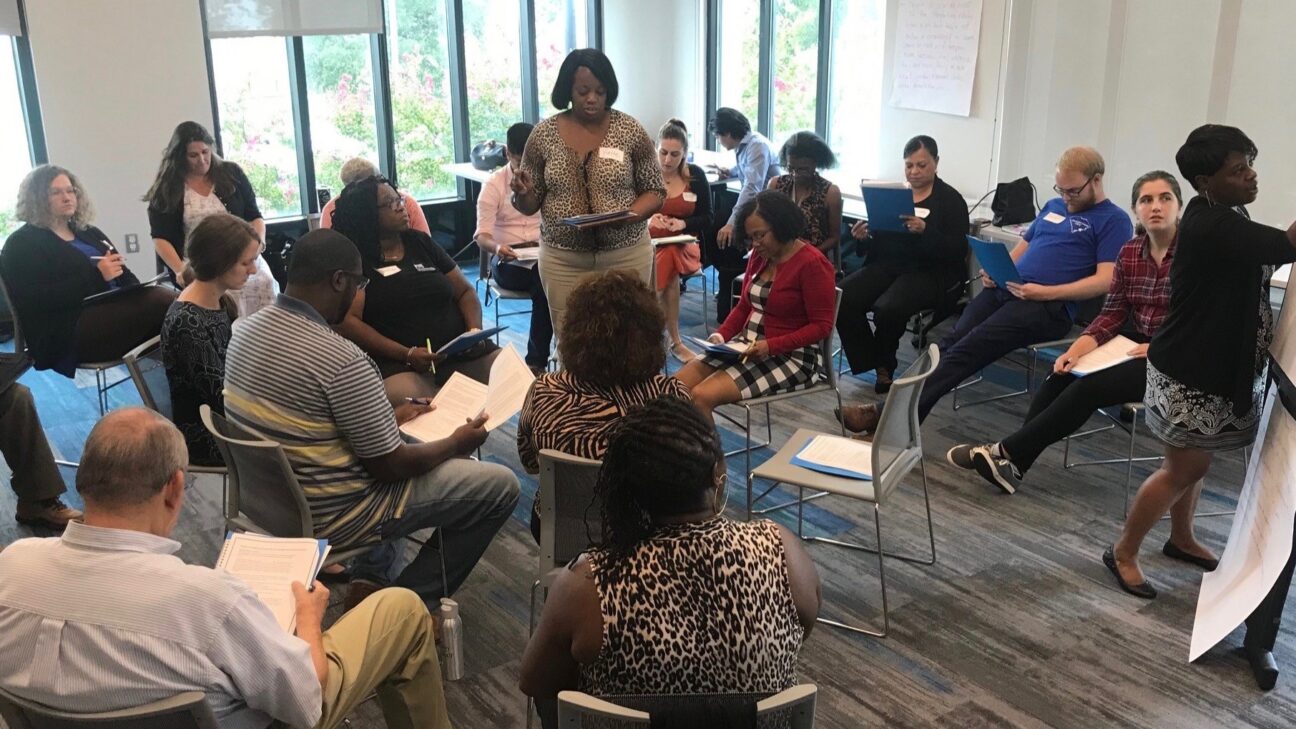

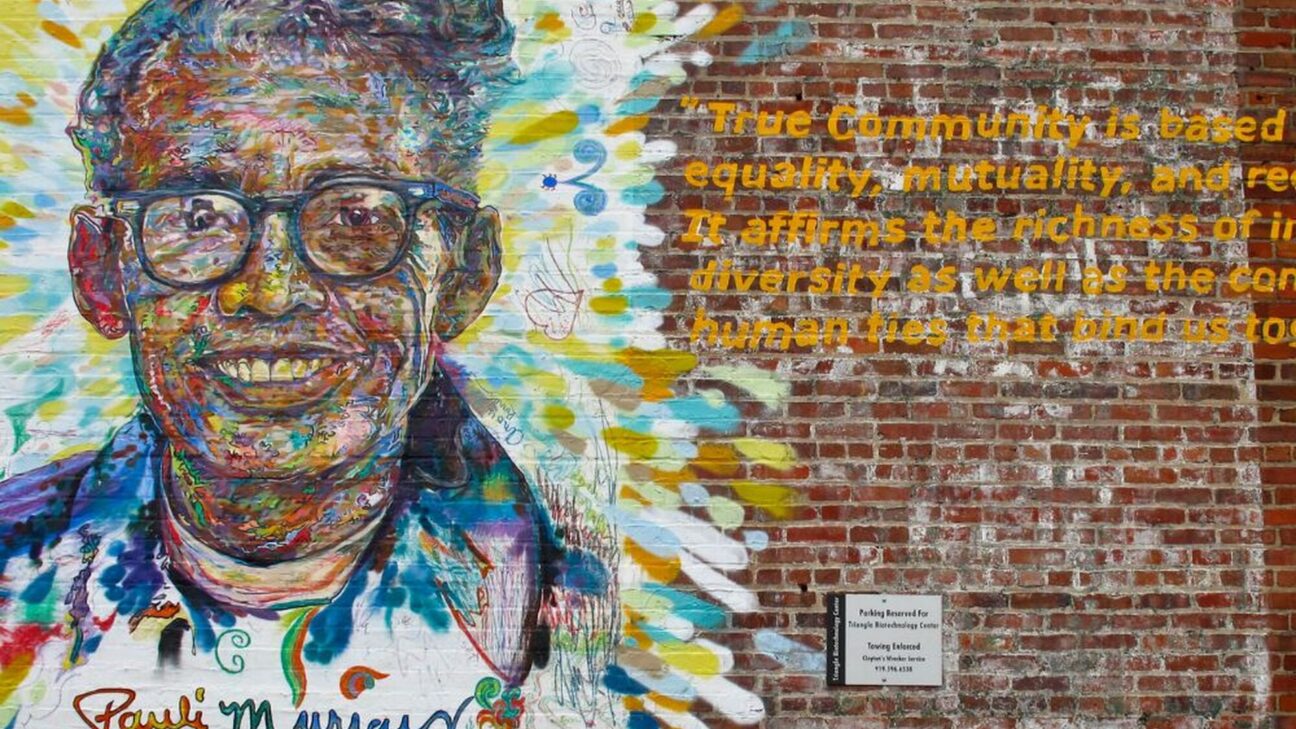

What Does Safety Look Like?

Photos from Dr. Gámez’ research collaboration with Flowers & Bullets.

Advice for Researchers

Dr. Gámez explains what researchers should consider before engaging and interviewing community members.